As you interpret Esther as a biblical character, let me encourage you to embrace complexity. Good narratives focus on dynamic characters, and scripture is replete with complex, multi-layered narratives. Rather than thinking in black and white, I’d encourage you to think in terms of layers. In short, characters can have layers of strength, layers of weakness, and layers in between.

(Note: I am not saying to reject binaries or absolutes; what I am saying is that literature invites us into deep, holistic, and rich readings—especially in regards to characters.)

Thus, rather than labelling Esther as “good” or “bad”—or “faithful” vs. “unfaithful”—we see displayed in Esther the full human condition. As many have mentioned previously, Esther was not perfect, and as New Testament readers, we know that “all fall short” of perfection. Perhaps some of her early actions could have been rejected, similar to how Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego took a stand in the face of danger. It’s often pointed out that she could be more brave or more faithful.

That being said, we need to be very careful about if/how we label her. Ultimately, it’s not our job to “judge” Esther, and really, her spiritual status is not the main point of the story. (In other words, people can have different views of Esther and still reach the same conclusions about the overall narrative.) Esther is complex, like all of us are, so labelling her as “all good” or “all bad” isn’t very helpful. Perhaps she willingly went along at times, but perhaps not; she could have hated her actions and the situation. To be frank, the narrative leaves some of that unknown, but just as you and I are “mixed bags”—within our collection of good gems we have some stones—so does Esther demonstrate the complexity of the human condition.

I point this out because we do not want to demonize Esther, as if she were a horrible Jew. As presented in the story, she is certainly not a villain, but a victim. She is held prisoner and has very few choices in front of her. (As my wife points out, Esther is portrayed as a “passive” character early in the narrative, while the men are the primary actors.) Again, she could have rejected the king, but very few would ever make that choice, given an impending death sentence. Especially due to the power imbalance—a king over a servant—it should be clear that she was objectified and used by the king. (A parallel is how King David misused his power over Bathsheba; he did not romance her, but abused her, prior to killing her husband.) Even though Esther is eventually “blessed,” the ends do not justify the means—so we can acknowledge that both victimization and elevation occur.

Thus, when the text says that the King was “pleased,” it does not mean that Esther fully embraced the role. Nothing in the text suggests that Esther enjoyed being in that position, so we don’t want to see Esther as “sinning” or being unfaithful in that situation. Even the preparation ahead of time does not mean she fully embraced the role, since she likely felt surrounded and stuck. Again, some aspects are unknown, but the silence raises a crucial point: it would be presumptive to say Esther sinned when the king took her, since as most ethicists would point out, immorality involves (unforced) personal will—not legitimate, threatening coercion from another, especially not by a person of power. (Note: Ethicists debate how much will is needed in the face of such coercion, such in as the infamous Patty Hearst case, so that could be debated.)

To state the issue more directly: In cases of sexual abuse, as well as potential cases being investigated, outsiders should focus on facts. We must be extremely cautious when assessing inner thoughts and motives of victims, since horrifically, it’s far too common for people to blame or shame victims. We should not presume anything. To use the parallel example of Bathsheba, rather than guess at her motives and blame or shame her, since the data is extremely limited, the focus should be on David’s atrocious behavior. Due to the incredible imbalance of power, regardless of anyone else’s actions, David wildly abused his position.

Literature commonly features “flawed protagonists,” since no one is perfect. Thus, regardless of the fine details (such as her motive or inner thoughts), we can embrace Esther as a “hero”—especially since other biblical heroes (e.g., Moses, David, Peter, Paul) acted far, far worse. I hope we don’t get “lost in the weeds” when debating Esther as an individual, since the author’s main focus is the overall success of the Jews, as enabled by God. Most importantly, no matter how we interpret Esther as a character, and no matter how many outstanding questions remain, what is certain is that God is the ultimate hero in this story.

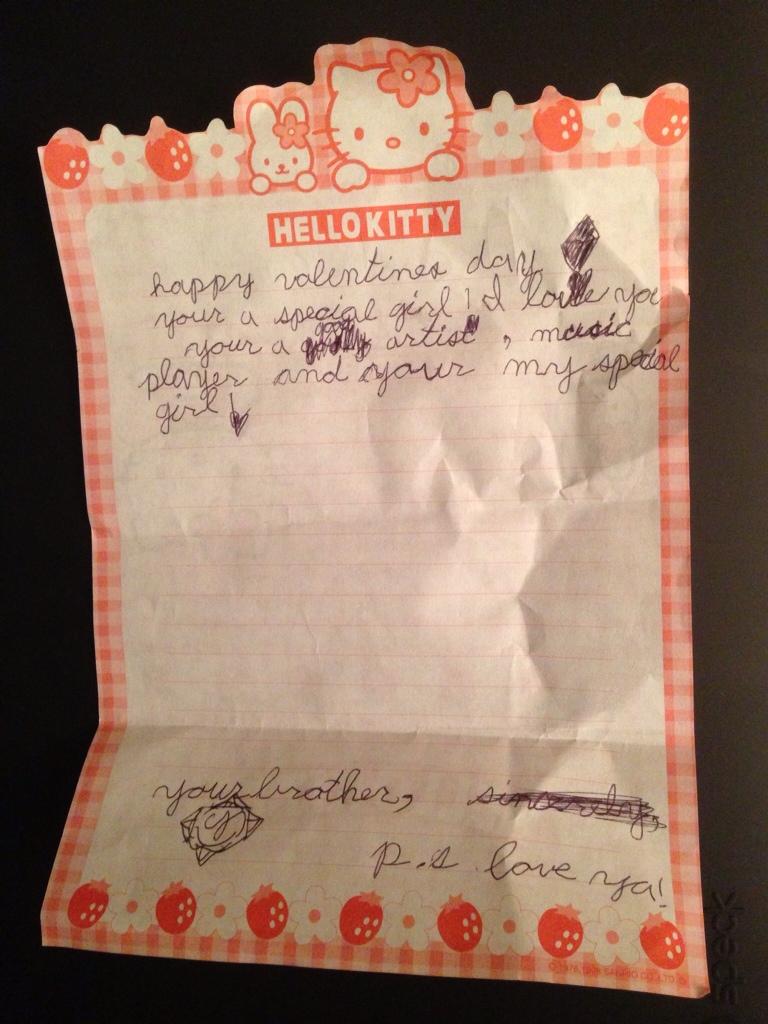

Whether or not you are in a relationship, holidays like these raise expectations so high that sometimes those expectations are impossible to meet. Today, some people will be let down because they are not in a relationship. Others will be let down for by their significant other, their fiance, or their spouse. The plain fact is that human beings eventually let us down.

Whether or not you are in a relationship, holidays like these raise expectations so high that sometimes those expectations are impossible to meet. Today, some people will be let down because they are not in a relationship. Others will be let down for by their significant other, their fiance, or their spouse. The plain fact is that human beings eventually let us down.