Persistent Prayer

One thought has sustained me over the past two weeks: Hundreds of believers around the world are praying for our family. With so much unknown before us, knowing of these prayers has been deeply comforting. Especially in the morning, when it’s easy to fear and hard to start another day, I remember your prayers. In my mind’s eye, I envision … Read More

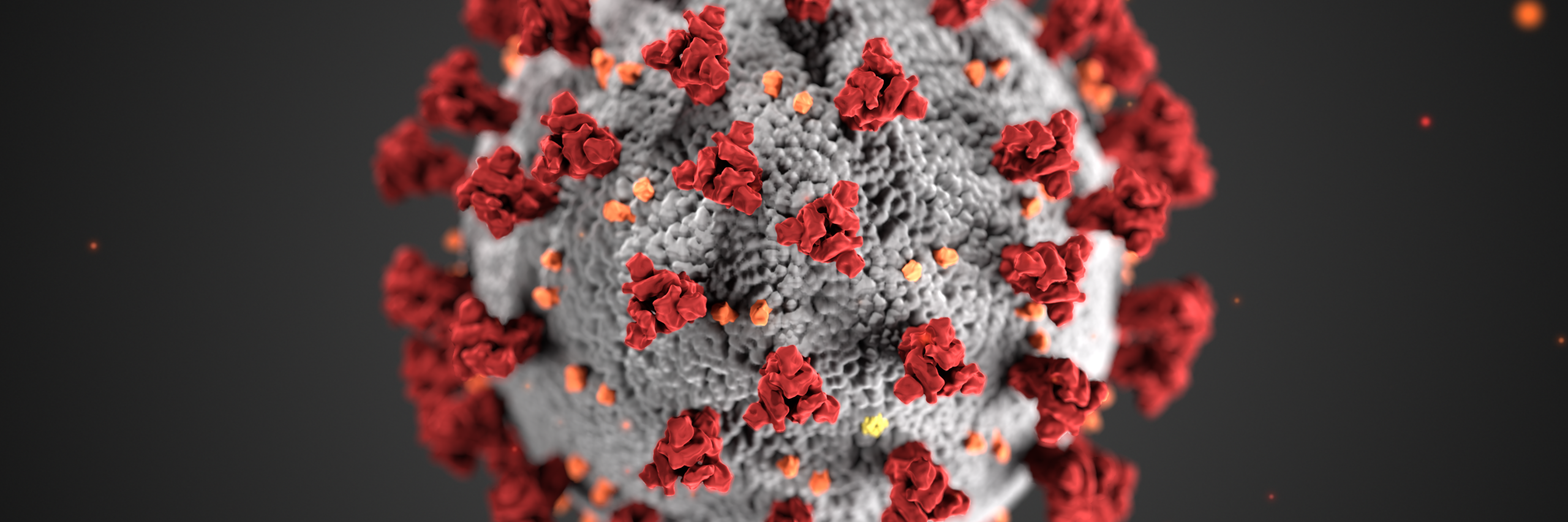

RESPONSE to Defiant Churches

To Churches Defying Medical & Political Leaders, Christians should be leading the way in terms of loving neighbors and exercising wisdom. Now that children and 30-50 year olds are known to be dying, there is no “safe” group per se. With that in mind, our witness can be damaged if we value ritual (even good rituals!) more than the innocent … Read More

Love, Liberty, & Caution: Why Jesus Would Wear A Mask

What’s most surprising right now is not the anti-science views circulating around the internet, but the callousness. There’s lots of debate, but less concern for the sick and the susceptible. All who fight for the “freedom” to not wear a mask overlook that the reason to wear a mask is for another person’s good, not their own. Good citizens, and especially people … Read More

COVID-19, Planning, & Jesus

As I observe dozens of Christians pondering what to do this weekend, I can’t help but ask: What would Jesus do? My guess is that Jesus would be out picking grain and delivering it to the needy — just like David took temple bread to feed the hungry. Both knew that life mattered more than tradition. The Sabbath, … Read More

How to Choose a Bible Commentary (Tips to Select the Best Commentaries)

I was recently asked some good questions about commentaries — basically, which ones are the best? To answer that, here are a few thoughts about which commentaries to use, as well as some practical advice to save you some money. Most scholars would advise not to buy a complete commentary set. This is because some volumes will be strong (even … Read More

The Purpose of Acts

The overall purpose of Acts is not to explain the Holy Spirt — i.e., as if Acts were a treatise on a single person of the Trinity. Yes, we could say the Spirit is the central character, and we can gather some theology of the Spirit from these narratives, but there is a much broader intent. After all, Acts is a … Read More

Promise in our Labor

Some of my favorite moments are when kids tell Bible stories. Today, I learned that Noah’s family had to cut down a lot of trees and that alligators are an in-between case, but probably made it onto the ark. And then there was a rainbow to show that God would not do that again, and Noah’s family had lots … Read More